It came to me the other day how much I miss thinking and writing about poetry. So I am back.

Into the gap left when The Writers Almanac took its hiatus—about which I will not comment—came The Slowdown, a daily email from former U.S. Poet Laureate Tracy K. Smith. (I can't imagine the pain of being poet laureate in the administration of the orange buffoon. But I also should not comment on that right now.)

Today's poem struck me in its simplicity and in its superb contrast of everyday images and objects with the poem's immense emotional weight. It's "A Joke About How Old We've Become," by Adam Clay.

The use of negatives to circuitously say something positive was the first thing that struck me about this poem. "Why not instead," "best not to fill," "how not to worry," "as if time won't eventually." The repetition of "not" in positive contexts gives the poem a sense of inevitability. But try as they might—and it seems they are trying—all these "nots" can't combat the one thing in the poem that is specifically "positive" but is the worst negative of all: the test results.

Negative space is the flip side of that negative language, and it's something I've rarely noticed in a poem. Often the shape of the lines can create negative space on the page, but instead, here the poet has created a number of empty spaces to be filled, or not filled, with words and images. He even says so in the middle of the poem: "sometimes it's best / ...not to fill / any space with words." There are many spaces in the poem, from the baskets hanging in midair to the body stretching, the space of the room to be crossed, "blank space" around the flag, the space of three decades, and the space "of stepping back we all do."

One form of blank space usually frowned upon in poetry as unnecessary is the homely article. How many poems have had all the "the"s and "a"s critiqued or edited out of them? A fair number of mine, anyway. But this poet uses articles as a way to slow the poem down, itself a "slow-draining sink," its weight seeping into the reader drip by drip. In one stanza, every line begins with "the," creating a rhythm: "the album... / the minor... / the room." We have not only "the plants" but also specifically "the plants in the hanging baskets." "The stars and the stripes." And most importantly, "the tests." Nouns in this poem are given their own space, their own weight, to settle in the reader's mind as familiar objects so that the speaker's fear and sadness are also familiar and become the reader's own.

My father's tests are positive, too. So maybe this poem speaks particularly loudly to me. I'd love to hear what you think of it.

The Craft of Copy

Why copy works—and doesn't.

Thursday, February 27, 2020

Friday, November 4, 2016

Forwarding Address

Now that I've gone freelance and have a website showcasing my work, I'll be posting over there. I suppose that if I have any major rants, they can live on this blog. Otherwise, find me at writeheidiwrite.com from now on.

Wednesday, April 13, 2016

Losing work is NOT a thing of the past

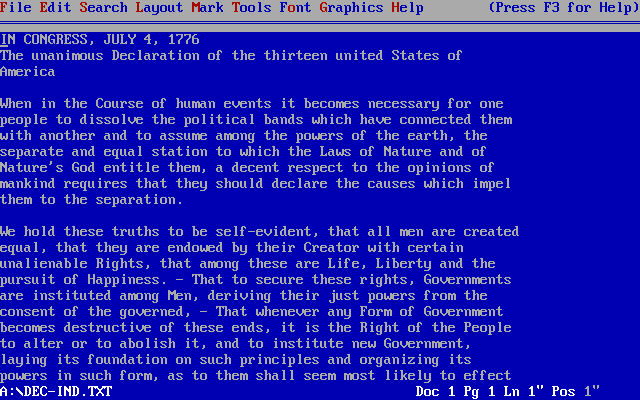

Remembering WordPerfect makes me feel old, but never having to ever use WordPerfect again makes me feel youthful and free. In the "olden days," typing merrily along (with my copy propped against a steel TypePal copy holder), I might accidentally hit the insert key instead of the delete key. There I'd be, blithely overwriting unknown quantities of characters, sentences, or paragraphs, instead of simply deleting one character and moving on.

Remembering WordPerfect makes me feel old, but never having to ever use WordPerfect again makes me feel youthful and free. In the "olden days," typing merrily along (with my copy propped against a steel TypePal copy holder), I might accidentally hit the insert key instead of the delete key. There I'd be, blithely overwriting unknown quantities of characters, sentences, or paragraphs, instead of simply deleting one character and moving on.Then there were random crashes, file naming errors (this was back when filenames were restricted to—I forget exactly—maybe 8 characters, and couldn't include spaces), and seemingly scores of other interesting ways to ruin your day by losing the work you'd done.

Today, I use Dropbox and a variety of other tools and I feel super safe about my work always being saved...but it's a false sense of security. Sure, my Word docs are backed up to Autosave all the time and to Dropbox at lightning speed, but that lulls a person, doesn't it? Makes you forget about the importance of constantly saving. Makes you forget about the difference between composing in Word and composing in a browser.

Makes you scream and whine bad words when you're trying to learn WordPress and you've been composing in the browser and suddenly you get a very nasty error:

Not Acceptableand then you just can't recover the post, no matter what you try. (Like, copying the entire text, intending to paste it into another doc, but then copying your password onto the clipboard just before deleting everything...)

An appropriate representation of the requested resource /public_html/wp-admin/page.php could not be found on this server.

Additionally, a 404 Not Found error was encountered while trying to use an ErrorDocument to handle the request.

Lucky for me, I won't have to rewrite much; maybe thirty minutes worth of work. Lesson learned.

Mostly. I'm actually composing this in the browser. Old dog.

Tuesday, March 22, 2016

Not the brightest coworkers.

My new coworkers are loud, demanding, and obnoxious. They're always hungry and always leaving poop on my doorstep. They interrupt conference calls with their cackling. This one even spies on me.

But they never drink the last of the coffee, and they don't break the printer, steal my pens, or load dishes incorrectly in the dishwasher. I think we'll get along just fine, after all.

But they never drink the last of the coffee, and they don't break the printer, steal my pens, or load dishes incorrectly in the dishwasher. I think we'll get along just fine, after all.

Monday, March 21, 2016

Chill out, already.

Another for the Lessons Learned file.

I got a lead on a healthcare copywriting project via LinkedIn ProFinder and applied; they responded asking me to bid the job. They provided most of the details, but not all; one item stipulated "some" sections to be written, but not how many.

I'd already mentioned that I might have questions, so I sent an email. But I couldn't just ask for clarification around the specific things I needed to know to finish the bid—no, no, that would be too easy. Instead, to show that I had experience in the industry and that I'd given the project a lot of thought (and because I simply wanted to know), I went ahead and fired off seven...SEVEN...additional questions. Including, to my chagrin, "would I have direct access to the client" for even more questions, once I was on the job.

Nice work, dumbass. Followed up today and, of course, they've "already got it taken care of." Because who wants an overeager show-off on their job, let alone asking for access to their client? Pro tip: Don't do that.

I got a lead on a healthcare copywriting project via LinkedIn ProFinder and applied; they responded asking me to bid the job. They provided most of the details, but not all; one item stipulated "some" sections to be written, but not how many.

I'd already mentioned that I might have questions, so I sent an email. But I couldn't just ask for clarification around the specific things I needed to know to finish the bid—no, no, that would be too easy. Instead, to show that I had experience in the industry and that I'd given the project a lot of thought (and because I simply wanted to know), I went ahead and fired off seven...SEVEN...additional questions. Including, to my chagrin, "would I have direct access to the client" for even more questions, once I was on the job.

Nice work, dumbass. Followed up today and, of course, they've "already got it taken care of." Because who wants an overeager show-off on their job, let alone asking for access to their client? Pro tip: Don't do that.

Monday, March 14, 2016

Could indenting make subject lines stand out?

I spent part of this morning working on an article about best practices for responsive emails in the pharmaceutical industry, a sort of 101 for pharma marketers. One section dealt with optimizing headlines. Then I saw this in my inbox:

The indented subject line really stood out in the list of emails, and I thought, how clever! But then I clicked on the email and realized that it wasn't a clever indent, it was emojis from which Gmail was apparently saving me. After having "read" the email, the emojis appeared in the subject line.

My spam folder shows me that emails with emoji in the subject line are usually screened, but I must have told Gmail that Ads of the World mail isn't junk. It made me wonder, though, about actually just using spaces in the subject line to indent it and make it stand out. As soon as I get my MailChimp account set up, I'm going to give it a try.

The indented subject line really stood out in the list of emails, and I thought, how clever! But then I clicked on the email and realized that it wasn't a clever indent, it was emojis from which Gmail was apparently saving me. After having "read" the email, the emojis appeared in the subject line.

My spam folder shows me that emails with emoji in the subject line are usually screened, but I must have told Gmail that Ads of the World mail isn't junk. It made me wonder, though, about actually just using spaces in the subject line to indent it and make it stand out. As soon as I get my MailChimp account set up, I'm going to give it a try.

Friday, March 4, 2016

"The flame beneath the pot"

Beautiful language can reach right off the page and startle you into a wide-awake, pleased wonderment, like a sudden kiss from someone you have a huge crush on. I read poetry in the hopes that I'll get that shivery rush.

Yesterday's Writer's Almanac poem, "Lobsters," by Howard Nemerov, did it. Even though the lovely turns of phrase are mostly morbid, I was enchanted with the powerful simplicity of the language.

These lines in the second stanza made me want to applaud: "Their velvet colors / Mud red, bruise purple, cadaver green." The perfection of the phrase "mud red": it simultaneously brings to mind "blood red" and also that absolutely correct muddy ochre color of lobsters. "Cadaver green" is a horribly delicious (sorry) irony, describing creatures whose bodies won't last long enough to be called cadavers.

The ending of the poem is very Yeats-ian, very "what rough beast," to me, but maybe that's because I just finished reading The Stand for perhaps the tenth time. (King seems to have turned this poem of 22 lines into a novel of over 1,000 pages). I won't spoil it; go read the poem.

Yesterday's Writer's Almanac poem, "Lobsters," by Howard Nemerov, did it. Even though the lovely turns of phrase are mostly morbid, I was enchanted with the powerful simplicity of the language.

|

| By GrammarFascist (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons |

These lines in the second stanza made me want to applaud: "Their velvet colors / Mud red, bruise purple, cadaver green." The perfection of the phrase "mud red": it simultaneously brings to mind "blood red" and also that absolutely correct muddy ochre color of lobsters. "Cadaver green" is a horribly delicious (sorry) irony, describing creatures whose bodies won't last long enough to be called cadavers.

The ending of the poem is very Yeats-ian, very "what rough beast," to me, but maybe that's because I just finished reading The Stand for perhaps the tenth time. (King seems to have turned this poem of 22 lines into a novel of over 1,000 pages). I won't spoil it; go read the poem.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)